A Deep Dive into the Complexities of Deep-Sea Mining

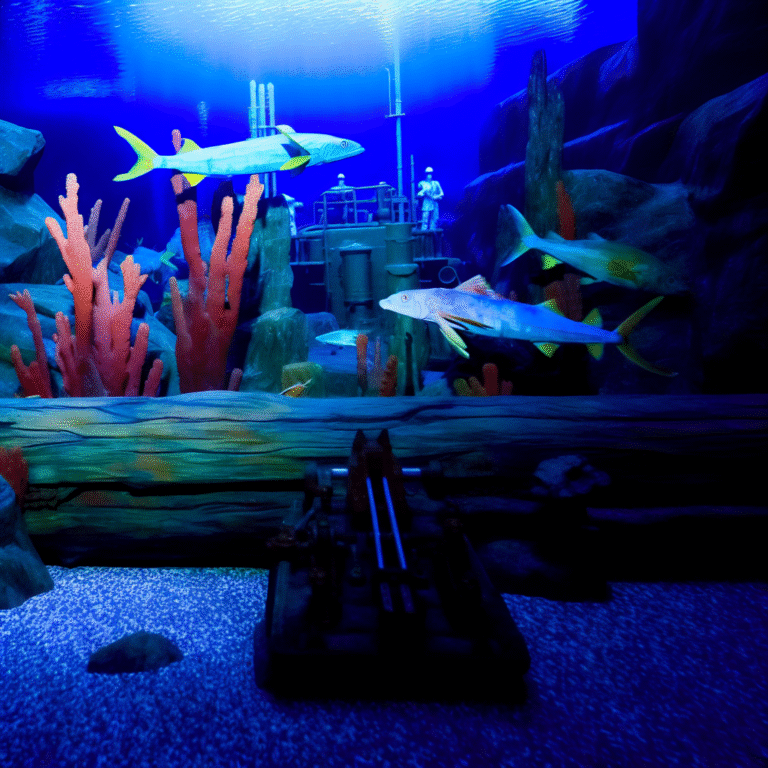

In unique marine territories—particularly those at depths of less than 200 meters, like the waters surrounding Greenland—geological processes have quietly at work for millennia. These processes have forged a treasure trove of metals essential to the green transition, stirring a confluence of commercial and political interests in the potential extraction of valuable resources such as cobalt, copper, nickel, and rare earth metals from the ocean floor.

However, this burgeoning interest is far from straightforward. The act of disturbing seabed structures poses significant risks to marine species inhabiting both the deep sea and the water column. Such tinkering threatens to disrupt biodiversity and the intricate ecosystems that rely on it.

In scientific discussions, there’s widespread consensus: the full consequences of deep-sea mining remain largely unknown. A technical note from Aarhus University’s Center for Environment and Energy underscores the pressing need for deeper investigation before any mining activities are permitted.

Calls for Caution in Greenland

As it stands, Greenland navigates a delicate phase regarding deep-sea mining. A moratorium, previously implemented by the former Naalakkersuisut, lapsed at the beginning of 2024. Current laws now allow for licenses to be issued for offshore operations, even in shallower waters.

Yet, for a ban on deep-sea mining to be enacted, amendments to the Inatsisartut Act are necessary. Naaja H. Nathanielsen, the Naalakkersuisut Minister for Business, Raw Materials, Energy, and Justice, is advocating for such a ban, although she acknowledges that the stance of other political parties on this contentious issue remains uncertain.

“I plan to propose a ban on deep-sea mining during this election cycle,” Nathanielsen stated. “While imposing a comprehensive ban on all marine mining activities could complicate projects involving glacier flour or sand extraction, I see no justification for allowing deep-sea mining. Our understanding of the potential ecological risks is too vague. Moreover, we have ample opportunities for land-based activities, which diminishes our need to explore the depths of the ocean.”

Nathanielsen is aware that any such proposal would require the backing of both the Naalakkersuisut and the Inatsisartut, marking a lengthy political process. “Currently, it’s a plan on my desk that I hope will garner the necessary political traction,” she added.

Navigating International Waters

At the recent “Raw Materials Week” conference in Brussels, Nathanielsen engaged in the broader international dialogue surrounding the complexities of deep-sea mining, which reveals a profound divide among nations.

“Some countries are enthusiastic about the prospects, while others express considerable concern,” she explained. “There are suggestions for a formal moratorium in international waters until the International Seabed Authority (ISA) lays down comprehensive regulatory frameworks for mining activities. However, progress on this front is slow, as consensus among ISA member states remains elusive. If Greenland were to join a moratorium in international waters, it would require unity within the Kingdom and a corresponding national moratorium, a conversation still in its infancy.”

As discussions evolve, the future of deep-sea mining continues to spark passionate debate both locally and globally, highlighting the intricate balance between opportunity and responsibility in our stewardship of the planet’s resources.