Marius Kristensen is one of the four adoptees from Greenland who are demanding compensation from the Danish state. A claim that has now been rejected.

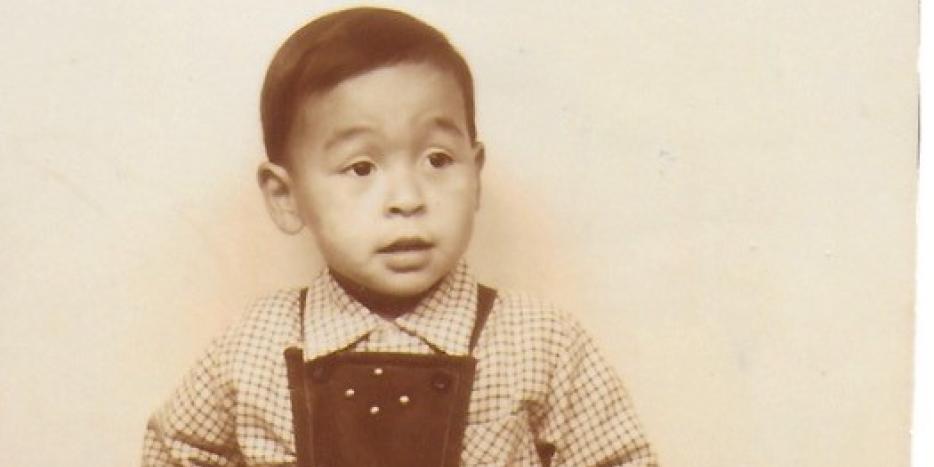

He was named: Marius Ludvig Johannes Elias Inûsugtok Jensen. A little dark-haired boy who was born in 1955 in the now defunct settlement of Aulatsivik south of Aasiaat.

If you took a look at the boy, who is now called Marius Kristensen, you might think that he was like most other Greenlandic boys. He was number six in a group of 12 siblings. From a family of hunters. He loved to run around in the mountains and played diligently with the other children.

But Marius Kristensen has felt different all his life. Like a Danish boy in a Greenlandic body. As a child, he was adopted by a Danish nurse who worked in Aasiaat.

That’s why Marius Kristensen didn’t speak Greenlandic, but Danish. At home, Danish food was served. His friends were the children of Danish teachers who had moved from Denmark to Aasiaat, and he often got into arguments with the local children. But one of the worst experiences was when an elderly Greenlandic woman aggressively called him a “traitor”.

– For many years I avoided thinking about where I came from. But I feel anger today that things have happened the way they have. I am angry that there has been a failure from the public sector. Especially from Denmark, but also that it has been allowed to happen in Greenland, he says.

70-year-old Marius Kristensen is one of four adoptees from Greenland who are demanding compensation from the Danish government. A demand they sent on National Day on June 21, 2024.

In total, the four people, represented by Pramming Advokater, are demanding compensation of 250,000 kroner each from the state for violating their human rights when they were removed from their biological parents.

But last week a letter from the Ministry of Social Affairs arrived with a message that was not as hoped for by the four adoptees. The Danish state has rejected the claim for compensation, as they consider the cases to be outdated.

At the same time, the ministry does not believe that there is sufficient documentation that the then applicable rules for adoption were not complied with in the four cases.

And that makes Marius Kristensen both angry and sad.

– The compensation itself is not that important to me. I’m more concerned with the fact that the authorities – society – acknowledge that something was wrong. So an apology would be really liberating for me to hear. An acknowledgement that something was really wrong in the social system at the time, and that is what is being apologized for.

Fostering turned into adoption

In the 1950s, when Marius Kristensen was born, tuberculosis was a serious problem in the country. Greenland had one of the world’s highest rates of the disease – and it also affected Marius Kristensen’s original mother, who had to travel to Denmark for treatment.

Therefore, she left Marius Kristensen, who was six months old at the time, in the care of the Danish nurse. But when Marius Kristensen was three years old, the care turned into adoption.

Adoptions in Greenland until 1979

Traditionally, adoptions in Greenland have taken place within the family, following the tradition of ‘gift children’ or foster children. The form is formally called ‘open adoption’, as the child and the biological parents know and often have a relationship with each other. In 1923, the Danish Adoption Act was put into effect for Greenland. The law is based on ‘closed adoptions’, where all ties and rights between the biological parents and the child are broken. In 1976, a new Danish Adoption Act was put into effect for Greenland. It tightened the rules for adoption and reduced the number of ‘closed adoptions’ in Greenland to a minimum.

Since the late 1970s, Greenland has had virtually no adoptions out of the country.

The Greenlandic Adoption Act was last amended in 2010 and currently includes three different forms of adoption: family adoption, stepchild adoption and stranger adoption. The first two forms of adoption are the most common.Sources: “Kinship and gender in Greenlandic urban communities – feelings of connectedness”, 2010 and the High Commissioner in Greenland and information from the Adoptionssamrådet.

Sources: “Kinship and gender in Greenlandic urban communities – feelings of connectedness”, 2010 and the Royal Commissioner in Greenland and information from the Adoptions Council.

“Grant for nurse (name, ed.) to adopt the child Marius Ludvig Johannes Elias Inûsugtok – Issued through the Governor of Greenland,” the adoption papers read in faded writing, followed by: “Free.”

Later in a typewritten document addressed to the King, Marius Kristensen’s adoptive mother writes: “The boy has been in my care since he was six months old, and it is now my wish to adopt him, so that he will bear my surname instead of InusutoK.”

But as a child, Marius Kristensen himself was unaware of the adoption papers he was later given as an adult. In fact, he didn’t even know he was adopted.

– For some reason, I didn’t dare ask how things were connected. So over the years, I went almost completely psychotic, wondering if my adoptive mother was my real mother. Or if the man she was married to was my father, because he was a bit dark-haired. It was completely crazy, because the differences were enormous.

Didn’t fit

A few years after Marius Kristensen was adopted, his adoptive mother met a Danish boyfriend who, like her, worked in Greenland. They soon had a child and decided to move to Denmark.

At that time, Marius Kristensen was 10 years old.

– I was a relatively lonely child and had difficulty feeling accepted. It was a difficult period. I did reasonably well at school because I was very confident in the Danish language, but I felt a lot of insecurity and distrust.

Marius Kristensen was particularly insecure at home. He saw his adoptive mother’s boyfriend as threatening and was afraid that he would hurt him.

– So when I lay down at night to sleep in Denmark, I thought several times that I should have a knife under my pillow so I could defend myself if he were to attack me.

Also in the city, Marius Kristensen quickly noticed that he stood out from the crowd. He was occasionally bullied at school, and there were “a few fights”. But the unpleasant comments came mainly from adults.

Like the time a tavern owner said, “Shut up man, you’re ugly”, from the bottom of his heart, adds Marius Kristensen and laughs a little.

– Many of the comments and things that have happened have made me have a basic experience that I was not good enough. I didn’t really fit in Greenland, and I didn’t fit in Denmark. I had an experience that I wasn’t like the others.

When he saw fellow countrymen on the street in Denmark, he often crossed to the opposite sidewalk. Because he felt disconnected from his origins.

– I was very ashamed of not being able to speak Greenlandic and at the same time afraid of being looked down on. That’s why I avoided other Greenlanders for many years.

A physical connection

But when his adoptive mother died, his homeland began to pull at him. Because with her death he also lost his adoptive family, and a longing was planted in him.

In 1986, he packed his bags and traveled to Nuuk to do an internship at Sana while studying to be a psychologist. And here he let the word out that he was looking for his original family.

– One day a colleague says there’s a woman waiting for me. My first thought was that I had forgotten an appointment, so I hurried away.

– The moment I walk through the door, there is a nicely dressed older woman and a younger woman sitting there. They were deeply touched when they saw me. The older lady then said that she was my mother.

For the first time in 30 years, Marius Kristensen saw his original mother and sister.

– And I didn’t doubt for a moment that it was right. I could feel it deep in my heart and in my stomach. It was an experience that we had a physical connection. I was just one hundred percent sure, he says.

More relaxed

It was as if a stone fell from Marius Kristensen’s heart when he met his family.

– It was a great relief. It meant that I am not alone. That there is a family that I come from. Since I suddenly had a family that welcomed me so lovingly and openly, I became more at peace as the years went by, he says.

Marius Kristensen spent the following years getting to know his family. He visited his mother and siblings, who had by then moved to Sisimiut. But with the new family also came a new story: his mother’s version of the adoption.

“Housewife (name, ed.) acknowledges her signature on the attached consent form, and declares that it is her wish that the child be adopted by the petitioner,” the old, yellowed adoption papers state.

But according to the mother, that’s not how it all happened, says Marius Kristensen. Because the mother said that she had not understood what the adoption entailed. Instead, she believed that Marius Kristensen was still in care, and not that she would not see her son again.

A story that recurs from several of the Greenlandic mothers who had their children adopted in the 1950s and decades ahead.

And that’s what prompted Marius Kristensen to demand compensation from the Danish government today.

– There has been a greater understanding and openness in society today towards the fact that bad things have also happened in the relationship between Greenland and Denmark. That the colonization by the Danish side has had some consequences, and now people are starting to look at those consequences and take it seriously.

Therefore, he is also disappointed that the Danish state is now rejecting the claim for compensation.

– What I notice in the rejection from the ministry is that they do not take into account the moral and ethical aspects. That is what is most hurtful. That they do not listen to the fact that there have been some mistakes along the way. For example, that my mother did not understand what she signed.