Greenland’s Economic Council recently published its report for the latter half of 2025, revealing a mixed bag of news for the nation’s economic landscape. Released on September 24, the report offers both a positive assessment and a cautionary tale.

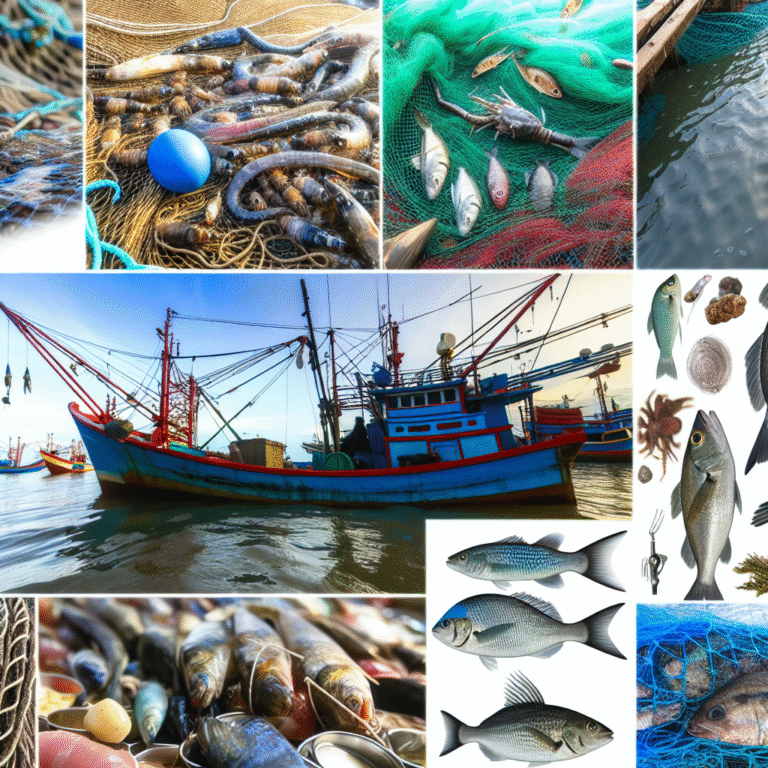

On the bright side, Greenland finds itself in a surprisingly resilient position amidst the tumultuous global economy, marred as it is by conflicts over trade and military engagements. The unique structure of our economy—characterized by a robust public sector and a dominant fishing industry—provides a layer of protection against external shocks.

However, the report also brings to light a more sobering reality. While Greenland’s economy continues to expand, the pace of growth has slowed considerably compared to previous years. This slowdown is attributed to dwindling fish catch volumes and the conclusion of significant airport construction projects. In light of our reliance on a narrow range of income sources, there is a pressing need to diversify our economic base. Expanding industries like tourism and mining could help bolster our economy alongside traditional revenue streams from block grants and shrimp exports.

“This dependency on fishing creates vulnerability for our economy until tourism and mining can fill the gap,” notes Torben M. Andersen, chairman of Greenland’s Economic Council, in an interview with Sermitsiaq.

While there have been years of favorable conditions in terms of both prices and quantities within the fishing sector, significant shifts loom on the horizon for 2025. The shrimp fishing industry faces challenges, with stock levels declining and prices under pressure—a situation that could reverberate across public revenues. Although the cod fishery shows promise, the coastal halibut sector remains mired in issues, grappling with both overfishing and the absence of Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) certification.

In a move to modernize the fishing industry, Naalakkersuisut has opened three ocean-going quotas for tender: 4,600 tonnes of halibut, 1,950 tonnes of cod, and an additional 166.6 tonnes of halibut in West Greenland. This decision stems from a desire to widen ownership and encourage new, often younger, players to enter the industry.

However, the Economic Council expresses concerns over the practicalities of this initiative. “Uncertainty looms over the effective utilization of these quotas,” the report states, especially with one-third being allocated to newcomers whose capability to make full use of the quotas remains questionable.

The challenges extend further, as the halibut fishery in the outer limits faces increasing quotas that could compromise its sustainability. In June, Naalakkersuisut raised the quotas in North Greenland to an alarming 35,786 tonnes, which is significantly higher than the scientific recommendations.

“Continued increases in the inland fishery quotas could jeopardize the MSC certification for our halibut, which is vital for maintaining price levels,” warns Andersen. He adds that while fishing conditions cannot be made entirely predictable, strict quota management and adherence to scientific advice could help mitigate the uncertainties.

It is concerning, he observes, that the Fisheries Act, aimed at fostering a sustainable fishery, has yet to gain serious traction within the political sphere. The halibut fisheries along Disko Bay, Uummannaq, and Upernavik are in a state of flux; over the years, the fishing stock has shown signs of decline, a reality underscored by the Norwegian Fisheries Council’s recommendations for drastic reductions in catch quotas.

Despite biological recommendations suggesting a total catch of 16,733 tonnes in 2025, political decisions have set the quota at 29,550 tonnes, with an alarming further increase announced in June—bringing the total quota to 35,786 tonnes. The politicians assure the public that such adjustments are isolated incidents; nevertheless, doubts linger.

Andersen stresses, “It is unfortunate that quotas are being increased at all. Maintaining a strict quota policy is a long-term benefit for everyone involved.” In light of past patterns where quotas have been raised mid-year, he calls for stringent adherence to historical quotas.

Naalakkersuisut justifies these elevation in quotas by citing an increase in the number of fishermen. At the beginning of the year, 1,199 active licenses were recorded in North Greenland’s coastal halibut fishery, comprising 120 small vessels and 1,079 dinghies. Since then, the influx of new entrants—31 additional dinghy fishermen in Disko Bay alone—has raised concerns among existing fishermen regarding their earnings potential. To address this, a moratorium on new licenses has been implemented, lasting from October 1 until January 1, 2027.

Yet, the Economic Council contends that the growing number of fishermen alongside rising quotas poses severe challenges. “While these measures may have political appeal, they do not foster sustainable growth in the fishing sector,” Andersen asserts.

The Fisheries Commission previously highlighted an oversaturation of participants in the halibut fishery, contrasting this with labor shortages in other sectors. Rather than entrenching individuals in unsustainable fishing practices, there should be efforts to transition them into other professions.

“Our resources are tied up in an industry that demands more labor than can be efficiently supported,” Andersen explains. “Redirecting those resources into diverse economic ventures would support a more self-sustaining and resilient economy.”

As Greenland navigates these economic waters, it faces a pivotal moment—one that will undoubtedly shape its future over the coming years.